NEW RISING HAIKU

The Evolution of Modern Japanese Haiku and the Haiku Persecution Incidents

Itô Yûki, Ph.D. (cand.), Kumamoto University, Graduate School of Cultural and Social Sciences

Monograph: Red Moon Press, May 2007

ISBN 978-1-893959-64-4

ABSTRACT

The following discussion focuses on the evolution of the “New Rising Haiku” movement (shinkô haiku undô), examining events as they unfolded throughout the extensive wartime period, an era of recent history important to an understanding of the evolution of the “modern haiku movement,” that is, gendai haiku in Japan. In his 1985 book, My Postwar Haiku History, the acclaimed leader of the postwar haiku movement Kaneko Tohta (1919–) wrote, “When discussing the history of postwar haiku, many scholars tend to begin their discussion from the end of World War II. However, this perspective represents a rather stereotypical viewpoint. It is preferable that a discussion of postwar haiku history start from the midst of the war, or from the beginning of the ‘Fifteen Years War [1931-45].’” A discussion of the situation of haiku during Japan’s extended wartime era is of great historical significance, even if comparatively few are now aware of this history. In fact, the wartime era was a dark age for haiku; nonetheless it was through the ensuing persecutions and bitterness that gendai haiku evolved—an evolution which continues today. Please note that the two predominant schools or ‘approaches’ to contemporary Japanese haiku are: 1) gendai haiku (literally: “modern haiku”), and 2) traditional (dentô) haiku, a stylism signally represented by the Hototogisu circle and its journal of the same name. To avoid confusion, the term “modern haiku” (in English) will indicate contemporary (1920s-on) haiku in general, while “gendai haiku” refers to the progressive movement, its ideas and activities. This essay also contains an added Addendum section: “Historical Revisionism (Negationism) and the Image of Takahama Kyoshi,” which details contemporary negationism concerning Kyoshi’s involvement in wartime persecution and his alliances with the Japanese Imperial‑fascist government, throughout the wartime era.

NEW RISING HAIKU

At 5:00 a.m. February 14th 1940, in Kobe city, in snowy weather, a plainclothes officer accompanied by two uniformed officers arrived at the home of Hirahata Seitô (1905-1997), a haiku poet and psychiatrist. The officers knocked hard, waking up the family. Dr. Hirahata was asked to come voluntarily to a Kyoto police office for questioning, concerning the haiku magazine Kyôdai Haiku (Kyoto University Haiku). The officer was a member of the Japanese Secret Police (tokubetsu kôtô keisatsu, or Tokkô), the Thought Police of the Imperial fascistic order of Japan; comparable to the Nazi Gestapo. With great trepidation, Dr. Hirahata pretended calm, moving toward the telephone. “Wait, just a second. I have to call my place of work, my hospital” he said, at which point the Secret Police officer informed him, “It is no use contacting your comrades, we have already arrested them all.” As Hirahata later reported, just at this moment his children innocently piped up, “Hi! Policeman have come to our house to play! Shall we play ‘police and thief’ with you?” not realizing the significance of the incident (Kosakai, 66‑7).

That February 14th was the first occurrence of wholesale arrests of the members of Kyôdai Haiku. Similar arrests of the magazine members occurred three additional times in 1940, from February to August. In total, sixteen haiku poets were arrested. This group included the notable poets Inoue Hakubunji (1904-1946?), Hashi Kageo (1910-1985), Nichi Eibô (1910-1993), Sugimura Seirinshi (1912‑1990), Mitani Akira (1911-1978), Watanabe Hakusen (1913-1969), Kishi Fûsanrô (1910-1982), and Saitô Sanki (1900-1962).

A year later, in February 1941, the Secret Police expanded their persecution to the members of the four “anti-establishment haiku” magazines in Tokyo: Haiku Seikatsu (Haiku Life) Hiroba (Field), Dojô (Above Earth), and Nippon Haiku (Japan Haiku). The victims of this persecution were thirteen poets, including Shimada Seihô (1882-1944), Higashi Kyôzô (also known as Akimoto Fujio) (1901-1977), Fujita Hatsumi (1905‑1984), Hashimoto Mudô (1903-1974), and Kuribayashi Issekiro (1894-1961).

Due to his treatment by the Secret Police while incarcerated, Shimada Seihô’s health deteriorated; he fell into a coma and later died. “Treatment” included various forms of torture, and the procuring of false written confessions, which included signed declarations such as; “I was an enemy of the government, but I now worship the Emperor,” and, “I was a Communist and planned revolution against the Emperor’s order,” etc. There were 22 separate clauses put into the false written confessions. Moreover, the haiku poets had to perform a “haiku anatomy” of their works—that is, they were forced to interpret and denigrate their works according to the will of the Secret Police. Prisoner-poets were also compelled to perform this “haiku anatomy,” on the works of their friends and fellow poets. Their magazines were also banned and burned. Today there is no extant copy of Kyôdai Haiku for February, 1940 but for a single journal serendipitously discovered among items left by a haiku poet who died during the war (Tajima, ii‑iii).

The collective series of arrests for the five haiku magazine-groups mentioned, from 1940 to 1941, is known the “Haiku Persecution Incident,” which unfortunately implies that there was only a single event. However, these persecutions continued throughout the war period—records show that 46 haiku poets (one woman and 45 men) were arrested. Two died due to inhumane treatment, and in the years 1940‑1945, over a dozen haiku magazines were obliterated.

As totalitarian governments in all times and places commonly persecute thinkers and artists, the activities related above might seem to fit a typical pattern. However, there is more to these incidents than mere persecution by the Secret Police. The targets of the repeated persecution were major haiku poets of the New Rising Haiku movement (shinkô haiku undô), who opposed the conservative haiku of the Hototogisu School and were attempting to write haiku with new subjects, utilizing terms and techniques which related to contemporary social life. To express such feelings, these poets frequently wrote haiku without kigo (season words), directly treated non-traditional subjects such as social inequality, and utilized modernist styles, including surrealistic techniques, etc.

One may wonder why not a single member of the largest and most influential haiku group, Hototogisu (or any traditional-haiku poet), was ever arrested. The answer is both shocking and embarrassing: Hototogisu was closely related to the Japanese Secret Police, and the Intelligence Bureau of Japan (jôhô kyoku). The conservative haiku poets persecuted the New Rising Haiku poets, utilizing the secret police. Furthermore, a number of notable traditional haiku poets were devoted to and actively promoted the fascist movement and the Japanese war effort.

Takahama Kyoshi (1874-1959), one of the two main disciples of Masaoka Shiki (1867-1902) and the leader of Hototogisu, became the President of the haiku branch of the Imperial‑fascist government culture‑control/propaganda group known as “The Japanese Literary Patriotic Organization (JLPO) (Nihon bungaku hôkoku kai),” which devoted itself to censorship and persecution, and other war crimes of various sorts. There are a few scholars who defend Kyoshi, suggesting that he was used by the fascist government, stating for instance that, “Kyoshi resisted the war via his attitude, in that he did not directly treat the war as a subject of his haiku in any way” (Asai, 146). This point of view will be discussed in some detail within the Addendum following this main text. It is an incontestable historical fact that as well as being President of the fascist JLPO Haiku Department, Kyoshi prominently served the causes of fascist cultural organizations and activities, and was deeply committed to the culture-control/ propaganda movement. At the time, the Director‑Trustee of the JLPO was Ono Bushi (1889-1943), who among his other professional titles was: kokumin jyôsô chosa iin, or: “The Agent of Investigation of the Minds of the Nation’s Citizens.”

An infamous statement published by Ono reads,

I will not allow haiku even from the most honorable person, from left-wing, or progressive, or anti‑war, groups to exist. If such people are found in the haiku world, we had better persecute them, and they should be punished. This is necessary (Kosakai, 169).

It was reported by one haiku poet who survived detention that he was commanded by the Secret Police (in the person of a Lieutenant Nakanishi) to “write haiku in the style of the Hototogisu journal” (Hirahata, 49; Kosakai, 79). According to the fascist-nationalist traditionalists, to write haiku without kigo (a traditional seasonal term), meant anti-tradition, and anti-tradition meant anti-Imperial order and thus high treason; therefore, all New Rising Haiku was to be annihilated. We are reminded of how the Nazis preserved so-called pure nationalist art, while persecuting the modern styles of so-called “degenerate art.”

Before discussing these incidents further and what lies behind them, I would like to give a brief overview of the history of haiku in the early 20th century. After Shiki’s death in 1902, haiku was divided into two main schools. Takahama Kyoshi insisted that haiku must be 17-on in a traditional 5-7-5 pattern (‑on are the phonemic sounds which are counted in Japanese haiku) with one traditional kigo, while by contrast, Kawahigashi Hekigotô (1873-1937) allowed free-rhythm and formal variation in haiku. Both schools continued to develop through the decades, however the style promoted by Kyoshi became more popular. He had inherited the Hototogisu journal from Shiki, who had revolutionized the genre, and this strong sense of lineage helped him succeed commercially. Kyoshi promoted haiku as a literature of kachôfûei (composition based upon the traditional sense of the beauty of nature). The Hototogisu School gathered together many haiku poets, fostered them, and became the strongest and most influential power within the haiku world.

The group known as the “Four S” haiku poets of Hototogisu are Takano Soju (1893-1976), Awano Seiho (1899-1992), Mizuhara Shûôshi (1892-1981) and Yamaguchi Seishi (1901‑1994). These four became leading figures in the haiku world of the 1920’s. The former two, Sojû and Seiho, penned excellent shasei (“sketch of life” haiku, a term coined by Shiki) and kachôfûei haiku, while the latter two, Shûôshi and Seishi, are most noted for their lyrical and romantic self-expression.

The new generation of haiku poets was growing in influence, yet Kyoshi as leader of Hototogisu had taken the stance of a tyrant from the beginning of his installment. In 1913, when he became the leader of the magazine, he published “The Commandment” (Kôsatsu) in Hototogisu. Within the text he declares, “Do understand and remember that Kyoshi is Hototogisu itself,” and, "Do oppose any new haiku style including the New Rising Haiku" (“Kôsatasu,” iv). Under his rule, there was literally no criticism of any kind allowed within Hototogisu, excepting for those critiques contained in the prose essays written by its leader. During this period, the “haiku world” meant Kyoshi’s world.

Due to a combination of Kyoshi’s authoritarianism and the promotion of fixed ideas in relation to haiku stylism, by the early 1930s Shûôshi and Seishi had departed the Hototogisu circle. In 1929, Shûôshi founded a new magazine, Ashibi (Andromeda flower), and in 1930, he published his first haiku book, Katsushika (so‑named after a downtown Tokyo location). At the time, it was an unwritten law that in order for a haiku poet to publish his first book, he or she needed to compile those haiku selected by Kyoshi, and had to beg Kyoshi to write an introduction. Shûôshi deliberately did not beg this introduction—an audacious action at the time. In the same year, Shûôshi published his own work of literary criticism, “The Reality of Nature and The Reality of Literature” (shizen no shin to bungei jô no shin) in his own magazine. In the essay, he states that that the objective shasei (Shiki’s “sketch of life”) conception alone is not a sufficient basis for the art of haiku, and that both creativity and wide‑ranging knowledge are necessary attributes for a haiku poet. Today, Shûôshi’s actions and statements may not seem all that remarkable; however, at the time these activities were considered not only innovative but were labeled “rebellion.” Ironically, the year of this haiku “rebellion” is the same as the beginning of the Fifteen Years War.1 In 1931, the Japanese Army invaded the northeast region of China, and the following year the puppet state of Manchuria was founded. The fascist‑Imperial movement progressed in parallel with the progress of the liberal movement of haiku. Kaneko Tohta comments on the haiku world and the sense of crisis during this period:

The beginning of the Fifteen Years War had nearly arrived. The period was a time of crisis for traditional ways of thinking, while for new, contemporary thought the period was a time of great possibility—accompanied also by great oppression. It was necessary for those grappling with novel modes of thought and art to articulate the feeling and zeitgeist of this era of crisis, to rebel against outdated concepts and thinking, in order to break through the realities of oppression and cultural stagnation, and for these artists to create new philosophies of their own. In such an atmosphere of crisis, the haiku world was filled with tensions between the old guard and new writers—it seemed that the conflict might even come to bloodshed. We can say that it was a time of great turbulence (haiku no honshitsu, 231).

The “rebellions” of Shûôshi and Seishi occurred during this year of crisis, mainly for the reasons indicated by Kaneko. The rebellions and the foundation of the new haiku magazine Ashibi were epoch‑making events. Influenced by this rebellion born from members who had been within Hototogisu itself, many new haiku magazines were consequently founded. In 1933, Kyôdai Haiku (Kyoto University Haiku) arrived, and in 1934 Hino Sojô’s (1901-1956) Kikan (Flag Ship) began. In 1938, Fujita Hatsumi (1905-1984) began publishing Hiroba (Field). As a result of this diversification, some magazines formerly allied to the Hototogisu School began to shift. Yoshioka Zenjidô’s (1889-1961) Amanogawa (Milky Way) and Shimada Seihô’s (1882-1944) Dojô (Above Earth) entered the new stream. As well, the haiku poets of Hekigoto’s free-verse school, including Kuribayashi Issekirô (1894-1961), joined the stream with his magazine Haiku Seikatsu (Haiku Life). Due to the mutuality and simpatico of the free-rhythm (jiyûritsu) school, the burgeoning movement was much enlivened. Taken as a whole, the new poetic styles represented by these magazines came to be known as the New Rising Haiku (shinkô haiku), one of the most significant origins of gendai haiku.

The vanguard of New Rising Haiku was the group and journal of Kyôdai Haiku. Young Kyoto University graduates had founded the magazine, but it soon became filled with the works of progressive haiku poets throughout Japan. Seishi encouraged the movement—its aim was to “overthrow the conservative haiku as season‑hobby literature, and to create gendai haiku as season‑feeling literature in the spirit of Bashô, and as true poetry” (Komuro, 48). Here is the Kyôdai Haiku declaration found in the first volume of the magazine, January 1933:

Now we present Kyôdai Haiku to the haiku world, which is the stream that pours through our hot youthful blood with the inheritance of the great poets of the past. Truly, when a person travels through the country of haikai [haiku], he cannot be indifferent to this pure stream. Some would avoid these waters, while others would quench their thirst with only a drop, as though with the sweet dew of a haikai ascetic journey. We make this clear avowal: our single wish is that this stream might irrigate the country of haikai forever (Tajima, 24-5).

The majority of these original poets were in their twenties or thirties; the New Rising Haiku movement was full of youthful energy. Their aims were modernism (composition pertaining to a sense of modern life), humanism (the betterment of humanity), realism (honestly facing social concerns), and liberalism (emphasizing the right to free expression). They often wrote haiku without kigo, and also wrote in free-rhythm/free-form styles. Moreover, they adopted an important social attitude, in managing their group without resorting to the traditional, feudalistic, master-disciple system. In their group all members were considered equal and free to engage in discussion and dissent. The magazine was also open to criticism from outside the group.

Such an attitude was quite liberal and innovative, particularly in that era. Japan was moving toward a fascistic order; nevertheless, the innovative magazine caused a sensation and sold well. The haiku below is a famous example from Kyôdai Haiku. While its aesthetic might be diminished in translation (losing the impact of free-rhythm, creative assonance, and cultural reference), the flavor of New Rising Haiku seems apparent:

水枕ガバリと寒い海がある 西東 三鬼

mizumakura gabari to samui umi ga aru Saitô Sanki

water cushion

chomp !

it’s a chilly ocean

Later, this haiku became Sanki’s epitaph.

Although many masterpieces were written, Japan sank into a dark age. In 1937, the Japan-China war began, closely followed by the rapid escalation of a massive ‘information war.’ The Japanese Cabinet Intelligence Bureau (naikaku jôhô-bu) was enlarged, and this Bureau and the army came to completely control all newspapers and other media. And the “All National Sprit Mobilization Movement (kokumin seishin sôdôin undô)” also began. In 1938, the “All Nation Mobilization Law (kokka sôdôin hô)” was enforced. Due to this law, the government was able to control various social activities. The imperial fascistic government began spreading propaganda, issuing statements such as: “This war is a Holy War in the name of the Emperor the living-god.” Japan was full of propaganda glorifying the war as a Holy War. Any information concerning the real battlefield was either concealed or glorified. The Nanjing massacre for example never became a matter of public knowledge.

The war and the propaganda campaign stimulated Japanese nationalism, and this nationalistic fervor hastened the advent of Imperial fascism. Many artists, including a number of haiku poets, praised the war as a Holy War and created the genre of “The Holy War Arts.” In 1937, Kyoshi became a member of the Imperial Art Academy (teikoku geijutsu in) for “The Holy War Arts,” and began a special serial-feature segment on the war, in ‘his’ Hototogisu journal, and even Shûôshi created a similar segment in Ashibi. At the time, Shûôshi had become strongly nationalistic—a stance over which, unlike Kyoshi, he later expressed apology and regret. They both published Holy War haiku anthologies; Kyoshi published The Collected Japan-China-War Haiku (Shina-jihen kushû), and Shûôshi published The Holy War and Haiku (Seisen to haiku) and The Collected Holy War Haiku (Seisen haiku-shû). Kyoshi and Shûôshi also gave radio lectures on “The Holy War Haiku,” and these lectures were compiled as The Selected Holy War Haiku (Seisen haiku-sen).

Kyoshi, notably, performed propagandistic activities not only in Japan but also in its then-colonies. In Korea, during a party held by the Japanese Intelligence Bureau, Kyoshi gave a speech in which he said, “The people of the Korean peninsula have had only weak minds from days of yore. As such, it is merciful to teach them Japaneseness and the awareness that they are Japanese, not Korean. Haiku is a good way to do it” (“Man-chô yûki,” 72). Clearly, Kyoshi’s notion was imperialistic, colonialist, and racially discriminatory.

The examples of Holy War Haiku shown below are representative, and cannot be described as artistic. In January, 1938, Kyoshi chose the haiku below as a “best exemplar” of Holy War haiku:

みいくさは酷寒の野をおほひ征く 長谷川 素逝 2

miikusa wa kokkan no no o ôi yuku Hasegawa Sosei (1907-1946)

The Holy War overwhelms

and progresses through

the violently cold field

One page four of the preface to The Selected Holy War Haiku, Kyoshi recommends this above haiku and offers a comment: “The warrior, who faces and overpowers enemies, even if they be demons and devils, has the Japanese feeling of respect for seasons and nature. This is the pride of the Japanese samurai.” Indeed, Kyoshi regarded himself as a samurai, and wrote the following haiku:

日の本の武士われや時宗忌 高浜 虚子

hinomoto no mononohu ware ya tokimune ki Takahama Kyoshi

I am a samurai

of Japan –

the anniversary of Regent Tokimune

Regent Tokimune (1251-84) was the commanding general (in effect acting Shogun, also known as Shogun Tokimune) who waged war against the invading Mongolian army of Kublai Kahn in 1274 and again in 1281. Both attempted invasions ultimately failed due to timely typhoons, hence Regent Tokimune has become an emblematic hero of wars fought against foreign armies. The word kamikaze (the wind of the gods, or “divine wind”) and folk beliefs such as “the kamikaze defends Japan from foreign armies” and, “Japan can never be defeated, due to the defensive power of kamikaze,” were born in this medieval era. In his haiku, Kyoshi identifies himself with this singular, semi-divine historical hero.

Shûôshi’s Holy War Haiku were more overtly nationalistic than those of Kyoshi. In his book, The Collected Holy War Haiku, Shûôshi writes,

In this Great Asia War, the attitudes of the enemy countries, in short, America, Britain, and other countries, are tremendously evil. In order to destroy such evil, our nation has arisen. From the very beginning of the war, our Imperial Army has severely damaged our enemies and incapacitated them. Yet you, the Japanese home-front citizens, should continue to unite your hearts with our Imperial Army to exterminate the evil (161).

When the Japanese Army conquered Singapore, Shûôshi penned this haiku:

春の雪天地を浄め敵滅ぶ 水原 秋桜子

haru no yuki tenchi o kiyome teki horobu Mizuhara Shûôshi

spring snow

purifies earth and heaven –

our enemies perish

The haiku below were published in 1940 by Shûôshi and Usuda Arô:

建国祭敵塁くづれ燃えに燃え 水原 秋桜子

kenkokusai tekirui kuzure moe ni moe Mizuhara Shûôshi

National Foundation Festival –

the enemy base falling

burns and burns

皇紀二千六百年の天の声 臼田 亜浪

kôki nisen roppyakunen no ten no koe Usuda Arô

Divine voice of heaven –

Divine Imperial Calendar 2600

Holy War Haiku tend to use technical terms related to the Imperial Order. National Foundation Day (kenkoku sai) in Shûôshi’s haiku above, is a national festival celebrating the First Emperor of Japan: the descent of the god (Jinmu Emperor) to the earth, believed to be February 11, 660 BCE. From the divine year of the arrival of the First Emperor, exactly 2,600 years had passed to the date of 1940 CE. Arô expressed this fact in his second line, above (kôki nisen roppyaku nen). National Foundation Day of 1940 was a huge festival, accompanied by parade music composed by the German composer Richard Strauss (1864-1949) and Italian composer Ildebrando Pizzetti (1880-1968), both deemed “authorized” composers by the Nazi Party and the Fascist Party (c.f. Shôwa: Nimannichi, vol 6). Although Holy War Haiku were inartistic, such haiku were written and published in uncountable numbers at the time.

In this atmosphere of war fanaticism and a controlled society existing under a fascist‑Imperial government, the New Rising Haiku poets wrote haiku with acuity, cruelty, strangeness and absurdity when addressing the topic of the war. They even expressed compassion with enemies. At the time, “non‑patriotic” (hi-kokumin) meant non-citizen, and writing haiku without kigo meant rebellion against the Japanese Imperial tradition. Even so, the New Rising Haiku poets expressed their own passions.3 The contrasts with Holy War Haiku can be easily discerned:

機関銃眉間ニ殺ス花ガ咲ク 西東三鬼

kikanjuu miken ni korosu hana ga saku Saitô Sanki

a machine gun

in the forehead

the killing flower blooms

戦死者が青き数学より出たり 杉村聖林子

sennsisha ga aoki suugaku yori detari Sumimura Seirinshi

war dead

exit out of a blue mathematics

枯れし木を離れ枯れし木として撃たれ 杉村聖林子

tareshi ki o hanare kareshi ki toshite utare Sugimura Seirinshi

leaving a dead tree

being shot as a dead tree

埋めてゐて敵なることを忘れゐたり 波止影夫

umete ite teki naru koto o wasure itari Hashi Kageo

during burial:

this is the enemy,

forgetting

To oppose such “non-patriotic” haiku as those above, in 1939 Kyoshi himself censored the comprehensive haiku anthology Haiku Sandaishû (The Haiku Trilogy), forcing the publisher to exclude the works of the New Rising Haiku poets (Furukara, 391-396; Hirahata, 58).

Finally, in 1940, the wholesale arrests began. The beginning of this persecution came through the betrayal of informers. Particularly from Hototogisu haiku poets, and especially Ono Bushi himself, who directly informed the Secret Police concerning the activities of the New Rising Haiku poets. The Secret Police set out the reasons for the arrests in an internal document, the Tokkô Geppô (the monthly record of Secret Police activities). The document for 1940, February, reads in part:

The magazine Kyôdai Haiku was founded by Lecturing Professor of Kansai University Inoue Hakubunji and a dozen other haiku poets in the eighth year of the Shôwa Emperor’s reign [1933], January. This magazine and the group opposed traditional haiku and insisted on haku without kigo and free-rhythm as the so-called New Rising Haiku. Advocating liberalism, they continued the publication of such haiku magazines. They attempted to inform readers about the validity of Communism through haiku based on “proletariat realism.” Asserting the protection of all classes and cultures, they struggled to promote anti-traditional haiku, anti-capitalism, and anti‑fascism movements. Furthermore, since the start of this Japan-China war, they have made an effort to publish haiku that are anti-war. They have attempted to attain their aims through such anti-war haiku (Tokkô Geppô: Shôwa 14 February 5).

The phrase “proletariat realism” was taken from the 1927 Comintern Thesis for Japan, which advocated the abolition of the Japanese Imperial regime. The Secret Police purposely linked this fairly‑forgotten terminological footnote of history with the fact that the New Rising Haiku poets wrote haiku on social life, in order to aggravate the appearance of offence—a violent misinterpretation, particularly as at the time none of the editors of Kyôdai Haiku were members of the Communist party (although some associated with the magazine had a strong sympathies with communism).4 Even had the haiku poets in question been the members of the party, the 1927 Comintern Thesis had been revised and replaced by the 1932 Comintern Thesis, with the slogan “proletariat realism” removed as outdated—eight years before the above‑quoted depiction had been written (Matsuo, 119-22, 146-47).

The Secret Police had the power to execute the haiku poets out of hand,5 but they took instead the tactical approach of the false written confession and “haiku anatomy,” as mentioned. Following the confession and “haiku anatomy,” and usually after a year or more of imprisonment, the Secret Police often sent the prisoner‑poet to the front lines of the war. Likely, this tactic had as an aim the avoidance of martyrdom via execution. Even if one were not sent to the front, haiku poets (and other progressive artists, liberal thinkers, religious and ethnic groups, minority populations, etc.) were imprisoned in filthy jails and were tortured. If let out of prison, the poets were put under Secret Police surveillance as thought criminals—plainclothes officers followed them at all times. If the individual under surveillance performed some “suspicious” act, the Secret Police re-arrested them, and once again torture ensued. Those under suspicion were also socially ostracized. It was not uncommon for entire families, including wives and children, to cut off all contact, and there are cases not only of divorce but also of family homocide/suicide (it remains unclear to what extent the Secret Police were complicit in these matters). Via such tactics, the Secret Police succeeded in producing many “converted” (tenkô) persons who became admirers of Japanese Imperial‑fascism.

Due to the persecution of Kyôdai Haiku, a great deal of fear arose among the New Rising Haiku community. Using this fear, Ono Bushi blackmailed a number of haiku groups and forced them to cease publication, as well as informing on them to the Secret Police. For example, the New Rising Haiku magazines Kikan and Amanogawa were terminated by Ono Bushi. Furthermore, in 1940 he founded the fascistic haiku organization, “The Japan Haiku Poet Society (Nihon haiku sakka kyôkai)” as a branch of the Intelligence Bureau. Kyoshi became the Chairperson of this organization, which not only promoted propaganda haiku but also sold thousands of pieces of tanzaku (a reed-shaped paper with a haiku written on it) and donated the collected money to the army and navy. The tanzaku of Kyoshi sold for a particularly high price: according to the official record in the 1942 Haiku Almanac, the donation was 6098.64 yen (Nihon bungaku hôkoku kai [JPLO], Haiku nenkan: Shôwa 17, 349). At the time, a pack of tobacco was 0.1 yen. By simple arithmetic, the donation would be worth approximately 18,295,920 yen, or some $175,000.00 USD today. The traditional-haiku poets’ tanzaku were changed into money, and then into bullets. This example is only the tip of the iceberg; many additional activities are worth relating, however space does not permit a fuller recounting.

In 1942, The JLPO (Japanese Literary Patriotic Organization; Nihon bungaku hôkoku kai) was founded, and affiliated the above-mentioned Japan Haiku Poet Society to it. The JLPO was quite deeply connected with the Imperial government and the Intelligence Bureau. In the JLPO’s foundation ceremony, Prime Minister Tôjô Hideki (1884-1948) and the President of the Intelligence Bureau gave congratulatory speeches. The foundation statement of the JLPO was: “We all, Japanese men of letters, should, by doing everything in our power, hereby establish a Japanese literature which embodies the Imperial tradition and ideals. We should praise and enhance Imperial culture. This is the aim of this Organization” (Tajima, 211). The President of the Haiku Department of the JLPO was, as mentioned, Kyoshi.

Also in 1942, the JLPO held the First Great Asia Writers Conference (daitô-a bungakusha taikai) in Tokyo. This conference consisted of the writers of Japan and its colonies and puppet-states: Manchuria, Korea, Taiwan, the Republic of China (Nanjing Government), and the Mongol Border Land (Mengjiang Government). Before the conference, the JLPO forced the writers of the colonies to go to the Meiji Shrine, the Yasukuni Shrine (the shrine now housing war criminals, which to the present annually causes consternation when officials present offerings there), and the Imperial Palace of Japan, as “a welcome tour” of the conference (Shôwa: Nimannichi, vol 6, 196-99). The route of the “welcome tour” was quite similar in style and intention to the welcome tour given the Hitler Youth in 1938 (Shôwa: Nimannichi, vol 5, 100‑02). At these places, the JLPO compelled the writers of the colonies to worship then-Emperor Hirohito, the divine soul of Meiji Emperor Mutsuhito, and the war dead of Yasukuni Shrine. The conference ceremony involved huge displays (as with the Hitler Youth rally). At the opening ceremony Kyoshi read his haiku for the conference as President of the Haiku Department of the JLPO (Shinbun Shûsei, vol 16, 460-61).

In 1943, the Second Great Asia Writers Conference was again held in Tokyo. In this same year Ono Bushi died due to illness, however the JLPO continued to control literary persons and societies. The JLPO committed drastic acts of censorship, for instance stopping the distribution of pen and paper to non‑patriotic writers, literally allowing pen and paper only for “the authorized writers.” In 1944, a Third Conference was held in Nanjing (cf. Bungaku Hôkoku). The JLPO demonstrated its great power and influence, both domestically and internationally. Few writers resisted the JLPO. On the contrary, many writers “voluntary” obeyed the dictates of this fascist-authoritarian organization.

The New Rising Haiku poets however retained their determined spirit. Even without pen and paper, even while imprisoned, they remained haiku poets. For example, in his prison cell, Higashi Kyôzô wrote haiku using a small piece of chalk, which he erased over and over again. Later, remembering 172 of the haiku he had written while in jail, these were published after the war. Upon the publication of this book, he changed his name to Akimoto Fujio. The Chinese characters of his name 不死男 (Fujio) mean, “an undying man.” In the haiku book entitled Kobu (A Lump), he writes: “During wartime, many people were inflicted with wounds. The wound I received, which was inflicted by the Haiku Persecution Incident, was merely ‘a lump.’ Even though it was but ‘a lump,’ I will never forget its pain” (Akimoto, 62).

Indeed, “the pain of the lump” embodied very difficult travails. While the spirit of these haiku poets was not extinguished, there was grievous suffering. The following two stories are representative: Inoue Hakubunji was sent to the frontline of the war when he was 42 years old. He was later captured by the Soviet Union army and never returned. Nichi Eibô, a skillful Russian interpreter and radio-wave engineer was captured by the Soviet Union’s GPU and sent to Siberia. He survived the Siberian gulag and torture. In 1950, when he arrived back in Japan, he was arrested by the CIA under suspicion of being a spy, due to his excellent Russian. In addition, he had given one of the infamous false confessions “admitting” he was a Communist, and this likewise caused suspicion, particularly given the period: 1950 was the start of the Cold War in Asia. In 1949, Mao Zedong’s Chinese Communist Party had gained power and founded the People’s Republic of China, while Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist Party of China (Kuomintang) and the Republic of China had decamped to Taiwan. Also in 1950, the Korean War broke out. It was on account of this strained political climate that Nichi Eibô was suspected. He was sent to the CIA offices of Kobe and Ashiya, given polygraph tests, and put under CIA surveillance until 1951 (c.f. Kosakai, 190-212).

Social hardships continued with the defeat of Japan on August 15, 1945. Emperor Hirohito pronounced the defeat on the radio at noon that day, and the democratization of the Japanese government began. The Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers (SCAP) disbanded various government organizations: the Ministry of War, the Secret Police, the plutocracies (zaibatsu), the JLPO, and so on. The Land Reform act was then instituted, allowing farmers and local populations to gain their own lands. In 1946, Emperor Hirohito declared that he was a human being and not a living‑god in “The Humanity Declaration (Ningen-sengen),”6 and according to Article 10 of the Potsdam Declaration, the Tokyo Tribunal of War Criminals was convened.

Even though the SCAP censored certain writings—for example, the publication of Saitô Sanki’s haiku about the atomic bombing of Hiroshima was banned (Kuroki, vol I, 62‑63)—Japanese writers, generally speaking, gained their freedom of expression, and in 1946 the New Rising Haiku poets founded the New Haiku Poets Association (Shin Haikujin Renmei). The 1947 Haiku Almanac (Ôno Rinka, ed., Haiku-nenkan: Shôwa 22), reveals the atmosphere of the haiku world at the time. Within the Almanac, reflecting upon the prewar era, the New Rising Haiku poet Higashi Kyôzô (Akimoto Fujio) summarizes the group’s original aim:

The New Rising Haiku movement was, in short, a movement to recover the adolescence of haiku. . . . In order to break the old and feudal tradition of haiku taste and thought, we hoisted the flag of liberalism and democracy against the exclusionism of the haiku world and the feudalistic master‑disciple system. That is, to create gendai haiku as poetry, we advocated the pure poesy of haiku, not the old hobby taste haiku (305).

On the other hand, in the same Almanac, the traditional-conservative haiku poet Usuda Arô states,

I sometimes hear mention that the master-disciple system of haiku is bad. However, such a notion is superficial. It may stem from an ignorance of haiku tradition. The outcome of the haiku spirit springs naturally from a great national love, which defines master as master and disciple as disciple. Therefore, this is the core of a “deep-and-high” ethical significance. Do not confuse the noble flowers with newly growing weeds. With my clear, pure, straight, and warm heart, I would like to pull out the stiff roots of the weeds, and throw away these tendrils, in order to comfort the noble flower. I do not lament or become angry without reason. I will remain as an observer, as facts are facts. But I, with you too, do reflect and think again—at the frosty window of December 8 [the Japanese date of the Pearl Harbor Attack] (ibid., 8).

Arô’s prideful statement reveals that he had not appreciably altered his views of haiku from his pre-war conceptions, and further, expressed a fairly militaristic or violent attitude toward gendai haiku; he embodies the mainstay conservative view of haiku at the time. Arô and other haiku poets, including Kyoshi, remained traditional-haiku authorities in the years following the war.

From 1946, “the weeds” or the New Rising Haiku poets began the “Prosecution for Haiku War Criminals” movement (haidan senpan saiban undô), a movement mainly led by the New Haiku Poets Association. Its advocates were Higashi Kyôzô (Akimoto Fujio), Furuya Kayao, several other haiku poets, and the lawyer, Minato Yôichirô (1900-2002). The movement’s aim was not to imprison those who had either instituted persecutions or collaborated with the Secret Police, but to justly and publicly cause those guilty parties to recognize the weight of their guilt and feel the sting of conscience. It was not a witch hunt. If it had been, the movement would have become a reverse mirror-image of the Haiku Persecution Incident(s). By contrast, the aim of the movement was “to resolve all the issues of the past in order to together hold hands for the progress of haiku” (Minato, 34). To attain this aim, it was felt that the defamatory actions of all haiku poets should be exposed and expressed, in public, and without delay.

In the January 1947 issue of the magazine Haikujin (Haiku Human), Minato Yōichirô presented a listing of the three main Articles defining Haiku War Criminal acts:

Article A. The crime of the formation of a fascistic haiku world as a leader of a fascistic organization.

Article B. The crime of leading the magazines that spread fascistic thought and co-operated in the unjust control of the haiku world.

Article C. The crime of the individual encouragement of the fascistic order and co-operation with the unjust control of the haiku world published via critical essays or works (36).

At the top of the list of haiku poets charged with committing crimes involving all three of the Haiku War Crimes Articles (A, B and C) are, in order: 1) Takahama Kyoshi, 2) Ono Bushi, 3) Usuda Arô, 4) Mizuhara Shûôshi, 5) Itô Gessô (1899-1946), and the list continues. There are 17 haiku poets listed in total (Ôno, Haiku Nenkan: Shôwa 22, 318).

An example of a poet listed under only Article B as a Haiku War Criminal is Katô Shûson (1905‑1993), whose magazine Kanrai (Cold Thunder) had an officer of the Imperial General Headquarters as a prominent member.7 An Article C Haiku War Criminal is, for example, Hasegawa Sosei (1907-1946), who published the war haiku collection Hôsha (Gun Carriage). The two haiku poets just mentioned, Kato and Hasegawa, both publicly offered their apologies. Of the five poets named above, at the top of the list of those charged with committing crimes under all the War Crimes Articles (A, B and C), none but Mizuhara Shûôshi ever offered an apology, despite abundant evidence detailing their profound complicity in war crimes.

As for Kyoshi, who acted as president of the various fascistic organizations, he made two statements some years later: “The war did not have any influence on the essence of haiku at all,” and “I will continue to write my haiku in the same consistent style” (Teihon Kyoshi Zenshû, vol 13, 407). Showing no regret, Kyoshi remained an important arbiter of the haiku world. Even today, he is sometimes referred to as “the haiku saint” (hai-sei: the same title as given to Bashô), and treated as though he were a demigod. There are several other conservative-traditional poets listed as Haiku War Criminals who have been treated in a similar fashion.

The “Prosecution for Haiku War Criminals” movement did not progress well. The main reason for this was that the master-disciple system of the haiku world was a major obstacle. The conservative-haiku poets offered an opposing argument of the master-disciple system theory. That is, that “the masters” of the New Rising Haiku poets were “the Four S” haiku poets, especially Seishi and Shûôshi. “The Four S” poets had originally belonged to the Hototogisu group, and hence “the master” of these poets would have to be Kyoshi. Therefore, in terms of lineage, Kyoshi is rightfully “the master” of the New Rising Haiku poets, and his “disciples” have as a result no grounds to object to Kyoshi. From a contemporary Western viewpoint, this theory may seem irrational if not totally absurd; nonetheless, this logic muted the whistle‑blowing. The liberal haiku poets at the time felt anger, but they could neither well refute the irrational logic, nor sway the haiku community with any real impact. In 1958, Saitô Sanki remarked, “Our teachers were from Hototogisu; we too, due to this link, are the disciple’s disciples—this way of thinking overwhelmed us and defeated us” (Tajima, 239). Via such irrational logic, the “Prosecution for Haiku War Criminals” movement finally dissolved.

Nonetheless, severe criticism came from outside the haiku world. In November, 1946, in the magazine Sekai (The World), Kuwabara Takeo (1904-1988), a scholar of French literature, published an article on haiku titled, “A Second Class Art: The Case of Gendai Haiku” (daini geijutsu ron: gendai haiku ni tsuite; gendai in this context means, merely, “contemporary”). In the essay, he presented a list of haiku without authors’ names given, and asked readers to find which haiku were authoritative and which were not, following the critical theory of I. A. Richards, who, to summarize, had insisted that the value of poetry should be found apart from any background context. This task proved to be quite difficult. Kuwabara argued that if haiku do not have “internal” value, then the haiku genre is neither poetry nor art. He wrote, “If you consider haiku to be an art, I recommend that you call it ‘the second class art,’ and discriminate between ‘the second class art’ and other fine arts” (85). Today this essay seems overstated; contemporary scholars do not seek to apply New Criticism to haiku, as the form is too short for proper application, and there are additional reasons, a discussion beyond the scope of this article. Notwithstanding, Kuwabara’s essay stemmed from his anger at the feudalistic attitude and hierarchy of the haiku world. He commented that,

Concerning modern haiku, it is difficult to define the status of a haiku poet by his haiku alone. Therefore the status of the haiku poet has to be defined not by the author’s haiku but by some other measure of status. In the haiku world [this is]: . . . the number of disciples, the circulation numbers of the magazine, and the power of the haiku poet as a measure of the haiku world. . . . For example, Kyoshi and Arô are not merely individual haiku poets, rather they are merely the Grand Master of Hototogisu and the leader of Shakunage. . . . They are feudalistic companions (76-7).

This essay caused a great sensation; though Kyoshi himself gave no response to it for seven years. On the other hand, Shûôshi responded: “Haiku cannot be appreciated by a person who does not write haiku” (Kuwabara, 73). Recalling that the master-disciple logic muted the whistle-blowing, it follows that if only an insider of the haiku world is allowed to criticize haiku, and if that insider’s voice can be suppressed by the power of the haiku authority—who then would there be available to criticize haiku? Shûôshi’s response reveals to us the feudalistic aspect of haiku world, and serves as well to explain Kuwabara’s tactics.

In contrast to the rather stark feudalistic atmosphere described, the haiku poet accused as an Article B haiku War Criminal, Katô Shûson, admitted with great gravity the historical mistake of the haiku world. He said that there had been a serious defect in the haiku world, “due to the fact that in the modern era, haiku had lost sense of the ‘human.’ . . . Why did haiku loose the sense of the ‘human’? The reason for this was the attitude of the haiku poets” (Kaneko, waga sengo, 127). Shûson’s words arose from his regret and apology for his wartime activity. Kyoshi, after his seven-year silence, made the following statement: “Haiku did finally become a second class art! This was good” (Kaneko, waga sengo, 85); this obtuse remark remained his only response.

Kuwabara’s polemic gave those involved in haiku the chance to think once again about the existing condition of haiku. In order to refute Kuwabara’s thesis, many haiku poets and scholars became inspired to write their own articles. Yamamoto Kenkichi (1907-1988) pointed out the uniqueness of haiku. In the same year of the publication of Kuwabara’s essay, he published a series of essays in the book, Greetings and Humor (aisatsu to kokkei). Within, he discussed the uniqueness of haiku and haiku culture from three viewpoints: the haiku party (kukai); greetings (aisatsu); unconventional humor (kokkei); and the time‑sense and effect of cutting words (kireji).

The first essay of the series is titled, “The Termination of the Sense of Time,” which states that the existent condition which formally connotes haiku is not 17-on, not kigo, but the kireji (the cutting-word). Deeply regarding the unique tradition of haiku, Kenkichi attempted to re-discover and re-define its value. In the same year, to refute the Kuwabara thesis via their own haiku compositions, young haiku poets gathered together and founded the magazine Kaze (Wind). The most notable member of this magazine was Kaneko Tohta, who became the principal leader of the postwar gendai haiku movement. In 1948, the New Rising Haiku poets also founded Tenrô (Wolf of Heaven).

In the first volume of Tenrô, Saitô Sanki ‘howls’:

Haiku does not arise from a lukewarm spirit, but rather from a blazingly adamantine spirit. . . . We were severely denounced and it was suggested that ‘haiku should perish.’ In order to affirm that ‘neither we nor haiku shall perish,’ we must deeply reflect on the spoiled and lukewarm attitude of the past era (Saitô, 20).

Indeed, Sanki did himself deeply reflect upon this theme. Sometime later, in his autobiographical writing, Kobe, Kobe Again, and the Tales of a Haiku Fool (1954-1960), he wrote,

The New Rising Haiku movement was destroyed by repeated persecutions. However, the New Rising Haiku poets were not exterminated. These poets experienced a time of forced silence after the persecution and the flames of war—both at the same time. During this period, the poets reflected on the development of the New Rising Haiku movement [and through their reflections made] . . . the discovery of the link between the spirit of the New Rising Haiku and those classic haiku on the bookshelf in an air-raid shelter (quoted in Kaneko, waga sengo, 94).

These reflections were inherited by the younger generation, especially Kaneko Tohta. Accordingly, in his view, the New Rising Haiku movement has continued to evolve into the postwar gendai haiku movement we know today. At the beginning of the postwar era, the New Rising Haiku poets, along with other like-minded poets, founded new groups such as the New Haiku Poets Association (Shin Haikujin Renmei), the Modern Haiku Association (Gendai Haiku Kyôkai), and the Association of Haiku Poets (Haijin Kyôkai). As well, the Hototogisu School founded the Association of Japanese Classical Haiku (Nihon Dentô Haiku Kyôkai), and the traditional haiku of Hototogisu remains popular today.

It is unfortunate that so many of the achievements of the New Rising Haiku poets should at this point in time lie buried within the dark history of the Imperial‑fascist wartime era. It may be that due to any number of uncomfortable events and facts, the creative advent and evolution of the New Rising Haiku movement has been neglected in comparison to traditional haiku, which in its history seemingly overleaps the wartime period in finding continuity with the Hototogisu School of an earlier, Shiki-inspired era. Though its wartime achievements, the gendai haiku movement has given us a great gift, allowing us to reflect on both the vitality and essence of haiku.

No form of literature is free from the changing conditions of its social context. My strongest motivation for the writing of this essay has been to relate historical facts to readers, especially those international readers who may be unaware of the context in which gendai haiku has evolved over the last century. The world of Japanese haiku remains vibrant today— its existence and value did not end in the medieval era of Bashô, but has continued to develop in both our real, literal lives and in our evolving aesthetic sensibility. Haiku is not merely a hobby, it is a literature. To create a good literature, one has to be honest with one’s heart, and haiku poets are no exception. The New Rising Haiku poets, in confronting tragic situations with a genuine and courageous heart, have created a poetic treasure which remains of value to all haiku poets and appreciators of culture.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

First of all, I wish thank Associate Professor Richard Gilbert (Kumamoto University), for his editing help and his encouragement. And I also owe my haiku teachers Morisu Ran, Hoshinaga Fumio, and the Modern Haiku Association my gratitude. I would also like to thank publisher Jim Kacian of Red Moon Press for the monograph, which has given this essay an international audience.

Japanese names are written in the family-name-first style. Also, the prose translations from primary sources are my own, and were co-edited to achieve their final form.

Historical Revisionism (Negationism) and the Image of Takahama Kyoshi

An icon of the traditional (dentô) haiku world, Takahama Kyoshi was one of the two main disciples of Masaoka Shiki, the leader and main force of the Hototogisu haiku journal and group, which brought haiku into the 20th century. As has been the case with several celebrated cultural figures in postwar Japan, forms of historical revisionism, and particularly negationism, “a process that attempts to rewrite history by minimizing, denying or simply ignoring essential facts,” has been at work for many decades now (Wiki: “Historical Revisionism”). Negationism concerning Kyoshi’s involvement in wartime persecution, racial discrimination, fascist nationalism, etc., throughout the 15-year wartime period in Japan (1931-45) has been instrumental in shaping his postwar image. The purpose of this Addendum is to present historical documentation of some of Kyoshi’s wartime activities, so that an accurately revised assessment of him can be made. Listed below are seven prevalent contemporary statements concerning Kyoshi, oft repeated as historical truth. The sources are left anonymous (it is not an aim of this article to single out any particular haiku school or cultural group). Each statement is followed by a commentary drawing upon relevant historical documentation.

Statement

1) Kyoshi was steadfast in his non-involvement in war mongering and was not involved in nationalism.

Comment

In fact, Kyoshi was deeply committed to war mongering and nationalist activities for many years. In 1937, when the Japan-China War started, Kyoshi began a special serial feature segment on the war in his Hototogisu journal. In 1939, he published war‑praising haiku in his edited anthology, The Collected Japan-China‑War Haiku (Shina-jihen kushû). He gave numerous lectures on “The Holy War,” not only in Japan, but in the then‑colonies and puppet states of Japan, including Korea, Taiwan and Manchukuo. One of his several radio lecture series, The Holy War Haiku Selection (Seisen haiku-sen), was published in 1942.

Statement

2) In 1954 Kyoshi was awarded The Medal of Cultural Merit (Bunka-kunshô), an award of great distinction. This esteemed award was never conferred upon anyone involved in World War II propaganda, persecution, or similar activities.

Comment

In truth, a number of those involved in wartime propaganda and persecution were awarded the Medal of Cultural Merit (this Medal is also known as the Order of Culture). This Medal or “Order” was founded in 1937 for renowned civilians (for soldiers, there was the Order of the Golden Kite (Kinshi Kunshô), established in 1890). The Medal of Cultural Merit can be conferred by the Emperor upon any renowned person.

For example, the General-President of the Imperial-fascist “Japanese Literary Patriotic Organization JLPO (Nihon bungaku hôkokukai),” Tokutomi Sohô (1863-1957), who was also a promoter of the ratification of the “Axis Tripartite Pact,” a Class-A War-Criminal, was awarded the Medal in 1943. (Sohô was held under arrest during the occupation of Japan, December 1945‑August 1947. The charges never came to trial, partly because of his advanced age. For further information, see, Sihn Vihn, Tokutomi Soho, 1863-1957: The Later Career. Toronto: University of Toronto-York University, Joint Centre on Modern East Asia, 1986). After the war, Sohô expressed deep regret concerning his commitment to the JLPO, returning the Medal in 1946.

There are others directly involved in wartime propaganda/persecution activities who have received the Medal. For example, Kobayashi Hideo (1902-1983) acted as a member of the special propaganda company of the Imperial Army, a group comparable to Germany’s “PK” (Propaganda Kompanie). In 1938, he first campaigned at the Battle of Whuhan, China, as a member of the Imperial Army’s propaganda company. During the war, he visited the battlefields and the occupied lands of China, Korea and Manchukuo several times for the Literary Home-front Movement (bungei jûgo undô). Along with his battlefield propaganda activities, he acted as one of the Director-Trustees of the JLPO Essay Branch. After the war, in 1967, he was awarded the Medal of Cultural Merit (cf. Etô Jun, Kobayashi Hideo, Tokyo: Kôdansha, 1961; Sakuramoto Tomio, Bunkajin tachi no daitôa sensô: PK-butai ga yuku [The Asia-Pacific War and Cultural Figures: The Campaigns of the Japanese “PK”]. Tokyo: Aoki-shoten, 1993). There are numerous additional examples.

Statement

3) Kyoshi has famously stated, “The war did not have any influence on the essence of haiku at all. I will continue to write my haiku in the same consistent style.” This statement has been interpreted to mean that Kyoshi’s haiku activity was free from the socio-political circumstances of the war; that he wrote haiku purely in kachôfûei style—a compositional style based upon the traditional sense of the beauty of nature and the use of officially sanctioned season words (kigo); i.e., those found within Hototogisu-published season-word dictionaries (saijiki). The implication of kachôfûei style then is that Kyoshi did not write within the “Holy War Haiku” genre (haiku which proselytized the war and Imperial‑fascism). The argument goes that true haiku are not influenced by socio-political circumstances, and therefore Kyoshi’s kachôfûei haiku are beyond the temporal world and history: such haiku are emblematic of “true” and “pure” haiku. A corollary to this logic is that the New Rising Haiku movement and its stylism perished, not due to persecution but rather because this movement and its poetics did not represent “true” or “pure” haiku.

Comment

Indeed, Kyoshi briefly discussed his beliefs in his Autobiography (Kyoshi jiden-shô):

Many newspaper and magazine reporters have caught up to and queried me. The questions posed were such as the following: “Did the war have an influence on haiku?” and, “What do think about haiku in the postwar era?” I answered, “The war did not have any influence on the essence of haiku at all. I will continue to write my haiku in the same consistent style” (Takahama Kyoshi, Teihon Takahamakyoshi zenjyû [The Entire Collected Works of Takahama Kyoshi], vol.13, Tokyo: Mainichi Newspaper Press, 1973, p. 407).

The two statements, “The war did not have any influence on the essence of haiku at all,” and “I will continue to write my haiku in the same consistent style,” quoted above, are known as “Kyoshi’s famous statement.” Notwithstanding, Kyoshi published not a few haiku during the war. For example, in the Hototogisu Journal of March 1942, he published his “Conquering Singapore” war haiku series.

It is shocking to discover that in the massive 15-volume collection, The Entire Collected Works of Takahama Kyoshi (1973-75), and in virtually all books one finds on Kyoshi, whether discussing his work or biography, his war-haiku works are completely excluded and his activities over the long wartime years are not mentioned, or at most lightly glossed. This purposeful whitewashing is a blatant example of negationism.

At the risk of stating the obvious, the New Rising Haiku schools did not perish. In fact, these poets resumed their creative activities after the war. The New Rising Haiku movement continued to evolve and flourishes today as the modern haiku (gendai haiku) movement.

Statement

4) Kyoshi directly protected and supported poets who were experiencing persecution by the Fascist government, such as Nakamura Kusatao (1901-1983), whom he protected from the Secret Police, at great risk to himself.

Comment

Some have it that, “When one of the Director-Trustees of JLPO, Ono Bushi (1889-1943), urged him to accuse Nakamura Kusatao, Kyoshi rejected this demand and kept protecting Kusatao.” However, this assumption is doubtful. Kusatao himself insists that Kyoshi warned Kusatao to: “Write haiku in kachôfûei style [the style of Kyoshi’s Hototogisu School] or you shall be arrested — do you know about the arrests in Kyoto and elsewhere?” Kusatao himself also reports that a Hototogisu haiku poet and one of the directors of the Imperial-fascist JLPO Organization, Tomiyasu Fûsei (1885‑1979), warned that “an arrest warrant for you [Kusatao] has already been issued.” When Fûsei presented these facts to Kusatao, Kyoshi was in attendance. So, the warning can be understood to be a threat. As a consequence of this warning/threat, Kusatao resigned from the Hototogisu group (cf. Kosakai, Shouzô, Mikoku: Showa haiku danatsu jiken [Betrayer/Informer: Showa era haiku persecution], Tokyo: Diamond-sha, 1979, pp. 170-85).

So, why was it that Kusatao was not arrested? The reasons do not have to do with Kyoshi’s intervention. In fact, Ono Bushi attempted to arrest Kusatao, collaborating with the infamous Secret Police high officer Abe Gengi (1894-1989), head of the Internal Ministry Secret Police Bureau (Naimusho Keiho Kyoku-chô). (Abe is listed as a Class A War Criminal by the International Military Tribunal for the Far East.) The arrest was never made, partly because Bushi was suffering from a severe illness, and also Abe Gengi was reluctant because his close friend, Umeji Shinzô (1885-1968), a scholar of physics, was opposed to it. To explain this relationship a bit further, Umeji was Kusatao's senior colleague (sempai) at Seikei High School (today’s Seikei University). Seikei High School was founded by the Mitsubishi Zaibatsu group as an elite educational institution with a seven-year course of study, and the teachers carried the title of “Professor.” As Professor Umeji Shinzo had high social status and was opposed to Kusatao’s arrest, the plot to arrest Kusatao was delayed and Bushi passed away during this interim. Kusatao thus escaped arrest by the Secret Police due to such happenstances. Concerning the case of Kusatao, Kyoshi never performed an act of heroism, or any such thing (cf. Ehime Newspaper ed. Nakamura Kusatao: hito to sakuhin [Nakamura Kusatao: his personality and works], Ehime: Ehime Newspaper Press, 2002).

Statement

5) Kyoshi had nothing to do with the suppression of the New Rising Haiku poets or movement, during the wartime period.

Comment

It is true that Kyoshi did not himself personally command the Secret Police to persecute New Rising Haiku poets. However, he maintained a strong attitude against the New Rising Haiku. In 1939, Kyoshi himself censored the comprehensive haiku anthology, Haiku Sandaihû [The Haiku Trilogy], ordering the publisher to exclude the all works of the New Rising Haiku poets. This was a direct action, but his indirect actions were much more significant. That is, Kyoshi was the center and main instigator of a neo‑fascist nationalist/traditionalist haiku ideology, which maintained a strong opposition to the New Rising Haiku. This ideology itself became closely allied with Imperial‑fascist nationalism, persecution, and the suppression the New Rising Haiku. Unfortunately, this ideology of intolerance, elitism and far‑right‑wing nationalism continues in some quarters today.

Statement

6) Kyoshi never expressed any regret concerning his wartime activities, because he did not commit any action for which an expression of regret was called for.

Comment

One wonders about Kyoshi’s sense of privilege and entitlement. When the air-raids became a fearsome burden, he moved to the rural countryside, Komoro, in Nagano Prefecture. In the countryside, he spent a quiet, pleasant time. However, he remained the President of JLPO Haiku Branch, and continued to earn a hefty salary from the Intelligence Bureau. Kyoshi’s negation of his own wartime activities may reveal a lack of a sense of social responsibility, a continuing belief in the appropriateness of his ideology, or both.

Statement

7) Kyoshi never used his Presidential post and/or artistic influence to glorify the war or government, and in fact he never spoke of these matters at all.

Comment

During the war, Kyoshi acted a chief member of several culture-control/propaganda organizations. In 1940, he became the President of Japan Haiku Poets Association (nihon haiku sakka kyôkai), which acted to control the haiku world for the promotion of “The Holy War.” In December 1941 (the month of the Pearl Harbor Attack, Invasion of the Malay Peninsula, Hong Kong, The Philippines, Thailand, etc.), he attended the Patriot Conference of Literary Writers (bungakusha aikoku taikai), and in a highly prominent role gave a historically significant speech, reading aloud “The Imperial Great Declaration of War against America and Britain,” in the name of the Emperor. Included in Figure 1, below, is a newspaper report of this event.

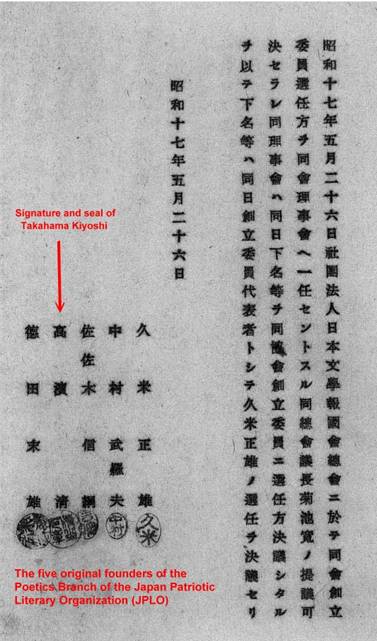

In 1942, the umbrella organization under the Fascist Intelligence Office, the Japanese Literary Patriotic Organization (the JLPO: Nihon bungaku hôkoku kai) was founded. Kyoshi was one of the five original signatories. See Figure 2 below, which is a photocopy of this document. Kyoshi then became the President of the Haiku Branch of the JLPO. One of the JLPO’s activities, which he organized, involved the raising of funds for the Imperial Army and Navy. Furthermore, as President of the Haiku Branch of the JLPO he attended the Great Asia Writers Conference (daitôa bungakusha taikai), which attempted to “reform” or “re-educate” writers in the Japanese colonies around Asia to become ‘good and worthy’ Imperial subjects. Kyoshi remained president of the Haiku Branch of the JLPO throughout the entire course of the war.

Postscript

Even a cursory examination of Takahama Kyoshi in relation to historical negationism reveals that Kyoshi these days is generally considered a heroic and indeed saintly figure, one whose actions and works are seen as worthy of esteem, both within the traditional haiku world and in the wider cultural arena. It is disturbing to discover the extent to which historical truths have been removed from the official record of his life (including educational textbooks). Indeed, an entirely fictitious picture of a “haiku saint” (an epithet with which he is often referred) has resulted.

The painful historical truths of Kyoshi’s life need to be acknowledged, along with the fact that Kyoshi has also left us haiku masterpieces. By way of comparison, it is worth considering the contemporary valuation of Western luminaries such as Ezra Pound and Martin Heidegger, who both advocated National Socialism; in Germany Heidegger famously joined the Nazi Party and informed on colleagues, while Pound preached National Socialism and Anti‑Semitism in Italy; both are held accountable and accessed concerning these activities, in the light of history. By contrast, Kyoshi’s involvement in Japanese Imperial‑fascism was much more direct and potent then Heidegger or Pound: he was a leader and policymaker, allied with the highest levels of the Imperial‑fascist government. In the West there has occurred a lengthy multi‑generational process of exposing WWII war criminals—the necessity for a public presentation of criminal responsibility for war crimes is an ethical given. In Japan, the exigencies of the Cold War and need for a rapid rebuilding of the country caused much to be swept under the rug, and this has partly resulted in a conspiracy of silence. Only of late, and after long delay, are certain uncomfortable wartime facts returning to light. We cannot and must not negate these historical truths. Kyoshi’s accomplishments in the field of haiku need to be evaluated within the wider context of his social and political actions, rather than in denial of them.

Figure 1. Takahama Kiyoshi Reads

The Declaration of War at the Patriot Conference of Literary Writers.

|

|

Reference Newspaper article and photo: Asahi Newspaper, December 25, 1941 (reprinted in Nihon bungakuhôkokukai [The Japanese Literary Patriotic Organization (JLPO)], Sakuramoto Tomio, Tokyo: Aoki Shoten, 1995, p. 63.)

1) Title: hotobashiru aikoku no netsujyô [An Outpouring of Patriotic Passion!]

2) Subtitle: kessenka no bungakusha taikai [Men of Letters Confer Under Decisive Battle]

3) Body text: first two paragraphs: “Joining under the great support of Taisei Yokusankai [the ‘right-socialist’ government of the Totalitarian State], one of the Cultural Persons’ Patriot Conferences, the Patriot Conference of Literary Writers, was held on December 24, at the third floor conference room of the Taisei Yokusankai Building. It began at 1:30 in the afternoon. Under the “Decisive Battle,” around 350 writers with ardent patriotic hearts gathered from the whole literary world: the poetry world, the tanka world, and the haiku world. It was surely an epoch-making conference, due to the mobilization of all these writers. As well, in order to create an exceptionally well-ordered totalitarian writers organization, [i.e. the “Japanese Literary Patriotic Organization (JLPO)”], 29 committee members were elected, including Kikuchi Hiroshi (a.k.a. Kikuchi Kan) (1888-1948). The Conference began with the “National Ceremony” — the salute, and worship in the direction of the Imperial Palace; the singing of the National Anthem; prayers of reverence and gratitude to the war dead; and, a silent prayer for the Imperial Army’s victories and fortune, followed by Takahama Kyoshi reading aloud of the “Imperial Great Declaration of the War against America and Britain” in the name of the Emperor. After Kyoshi’s reading of the Declaration of the War, speeches of praise were made by the Vice-President of Taisei Yokusankai, Ando Kizaburo (1879-1954), and the President of the Intelligent Bureau, Tani Masayuki (1889-1962) this was followed by …” [emphasis mine]. |

|

Body text: Last four lines: “Following the Conference, the writers were arranged in three quads, and paraded to the Imperial Palace from the Taisei Yokusankai Building, in four columns; and in front of the Imperial Palace, the attendant writers all shouted “banzai” [long life to the Emperor!] three times, and thus the conference was party was completed, with this deeply heartfelt expression.”

Please note that at the green 4) the name “Takahama Kiyoshi” appears. (Additional notes to Figure 1 follow the “Endnotes” section, below.) |

|

Figure 2. Takahama Kiyoshi: One of five founding members

of the Imperial‑fascist JLPO Foundation Committee.

|

|

Title: Nihon bungaku hôkokukai, dai nippon genron hôkokukai: bungakuhôkokukai setsuritsu kenkei shorui [The official documents of the foundation of “The Japanese Literary Patriotic Organization (JLPO)” and “Japan Patriot Literary Speech Organizations”], (Kansai University Library (ed.), Osaka: Kansai University Press, 2000, vol. 1, p. 69.)

Text: On Showa 17 (1943) May 26, at the Supreme-General Conference of the Japanese Literary Patriotic Organization (JLPO), the following issues were decided, according to the opinion of the chairperson Kikuchi Hiroshi (a.k.a. Kikuchi Kan, 1888-1948): The appointment of the Foundation Committee was authorized by the Council. The Council appointed the following five persons [listed on the left, with personal signature seals]. The Foundation Committee members elected Kume Masao (1891-1952) as their representative, on the same day (Showa 17, May 26).

[The Foundation Committee members’ real names (not pen names) with their seals are on the left side of the page. They are]: Kume Masao (1891-1952) Nakamura Murao (1886-1949) Sasaki Nobutsuna (1872-1963) Takahama Kiyoshi (Takahama Kyoshi) (1874-1959) Tokuda Sueo (Tokuda Shûsei) (1872-1943)

Please note that: 高濱清Takahama Kiyoshi: real name. 高濱虚子 Takahama Kyoshi: pen-name.

This document reveals that Kyoshi (Kiyoshi) was a chief founding member of the JLPO Foundation Committee. |

APPENDIX 1

List of the 46 Arrested Haiku Poets

|

February 14, 1940: First wholesale arrest of Kyôdai Haiku

井上白文地 Inoue Hakubunji (1904-1946?) 中村三山 Nakamura Sanzan (1902-1967) 宮崎戎人 Miyazaki Jûjin (1908-?) 新木瑞雄 Araki Mizuo (1918-?) 辻曽春 Tsuji Sôshun (1892-?) 平畑静塔 Hirahata Seitô (1905-1997) 波止影夫Hashi Kageo (1910-1985) 仁智栄坊Nichi Eibô (1910-1993) (岸風三楼 Kishi Fûsanrô (1910-1982))8

May 3, 1940: Second wholesale arrest of Kyôdai Haiku

石橋辰之助 Ishibashi Tatsunosuke (1909-1948) 杉村聖林子Sugimura Seirinshi (1912-1990) 三谷昭 Mitani Akira (1911-1978) 渡辺白泉 Watanabe Hakusen (1913-1969) 和田辺水楼Wada Heisuirô (1906-1980) 堀内薫 Horiuchi Kaoru (1903-1996)

August, 1940: Third arrest of Kyôdai Haiku

西東三鬼 Saitô Sanki (1900-1962)9

February, 1941: Wholesale arrest of the four major New Rising Haiku groups

Dojô 島田青峰 Shimada Seihô (1882-1944) 古家榧夫 Furuya Kayao (1904-1983) 東京三 Higashi Kyôzô (a.k.a. 秋元不死男Akimoto Fujio) (1901-1977)

Hiroba 藤田初巳 Fujita Hatsumi (1905-1984) 細谷源二 Hosoya Genji (1906-1970) 中台春嶺 Nakadai Shunrei (1908-?) 林三郎 Hayashi Saburô (1907-?) 小西兼尾 Konishi Kakeo (1906-?)

|

Nippon Haiku 平沢英一郎 Hirasawa Eiichirô (1889-?)

Haiku Seikatsu 橋本夢道 Hashimoto Mudô (1903-1974) 栗林一石路 Kuribayashi Issekiro (1894-1961) 横山林二 Yokoyama Rinji (1909-?) 神代藤平 Kamiyo Tôhei (1902-?)

November, 1941: Wholesale arrest of the Yamanami group

山崎青鐘 Yamazaki Seishô (1907-?) 山崎義恵Yamazaki Yoshie (?) 西村真青Nishimura Masao (1909-?) 前田北四季Maeda Hokushiki (1912-?) 鶴永想峰Tsurunaga Sôhô (1914-?) 勝木茂夫Katsuki Shigeo (1913-?) 紀藤章文Kitou Akifumi (1915-?) 福村信夫 Fukumura Nobuo (1909-?) 宇山樹Uyama Itsuki (1915-?) 和田冬湖Wada Tôko (1906-?)

June, 1943: The wholesale arrest of the Kirishima and Ujiyama-Keitoujin-kai groups

Kirishima 瀬戸口武則Setoguchi Takenori(1913-?) 面高秀Omodaka Shû (1904-?) 大平寛夫Ohira Hirô (1905-?)

Ujiyama-Keitoujin-kai 野呂新吾Noro Shingo (1901-?) 福田三郎Fukuda Saburô (?)

December, 1943: The arrest of the Sasoriza group

加才信夫Kasai Nobuo (1911-1946) 高橋紫衣風 Takahashi Shiifû (1917-?)

|

ENDNOTES

1 The series of wars initiated by the Imperial-fascist government of Japan, 1931-1945, from the battle of Manchuria to the end of the Pacific War.

2 Hasegawa Sosei (1907-1946) was a graduate of Kyoto University and a founding member of the Kyôdai Haiku group. He insisted upon applying traditional haiku style, and left the group, entering the Hototogisu School and then, the front-lines of the war. On the battlefield he wrote many war haiku. His war haiku collection was published as Hôsha (Gun Carriage). Due to Kyoshi and other haiku poets' praises, his book became a bible of Holy War Haiku, and as a result greatly promoted Holy War haiku. After the war he was accused as a Haiku War Criminal; however, some of his works can also be read as anti-war expressions. His valuation remains controversial among scholars today.

3 These examples along with others have been co-translated by myself and Richard Gilbert (Associate Professor, Kumamoto University), and have appeared in NOON: Journal of the Short Poem 4 (Philip Rowland, ed., Tokyo, 2006).

4 The disciples of Ogiwara Seisensui (1884-1974), the free-verse haiku poets Kuribayashi Issekiro and Hashimoto Mudô, together founded the Proletariat Haiku Poets Association (puroretariahaijin dômei) in 1931, and their journals were banned five times—including Haiku Seikatsu, whose publication was the immediate cause of arrests undertaken by the Secret Police (Asano, 147).

5 “The Peace Preservation Law (chian iji hô),” went into force in 1925 for the persecution of communism, was strengthened in 1928 and once again in 1941 to include the persecution of any liberal thoughts which could be against “The Imperial Order (kokutai).” In the first article, the law clearly states that any crime against “The Imperial Order” is punishable by death. Using this law, the Secret Police arrested many people. However, the Secret Police tended to produce “converted” people rather than perform executions. According to the record of the Shihô-shô (the Ministry of Justice of Japan during the wartime constitution), the number of victims of this law were listed in the following statistics: 75,681 people were sent to prosecutors, 5,162 people were indicted. There was no record of execution under this law. However, the above statistics deal only with the numbers of the people who were “officially” sent to prosecutors. There were many unrecorded arrests and victims. In fact, the name of the haiku poet Kishi Fûsanrô is not recorded in the “official” record of the wartime government. According to the statistics given by the League of the State Compensation Requirement for the peace Preservation Law Victims (chian iji hô giseisha kokka baishô yôkyû dômei), 65 people were killed extra‑judically, 114 died due to torture, 1,503 died due to disease caused by filthy prisons, and half a million people were arrested. As well, in Korea, Taiwan, Manchuria, and other colonies, many people were arrested, and many were tortured and executed under this law.

6 The draft of “The Humanity Declaration” in English was written by R. H. Blyth, the very author who published the four volumes of Haiku (1949-52), which did much to bring about a North American renaissance in haiku.

7 During wartime, the censorship of the haiku magazine Kanrai was relatively loose because an officer of the Imperial General Headquarters was a prominent member. Therefore, to an extent, the magazine was able to serve as a place to foster the younger generation, including Kaneko Tohta. However, after the war, the relationship with the army was revealed, and many young haiku poets left the magazine. The incident was led by Harako Kôhei, (1919-) and called “a tiny coup” (Kanekao, Waga sengo, 97). Throughout the resulting turbulence, Kaneko Tohta remained at the magazine for a time, playing the role of mediator between the sides of Shûson and Kôhei.

8 He was soon released, and not listed in the Secret Police Journal, so some scholars do not count him as a victim.

9 He was suspected of being a spy not by such agencies but by his friends. Sanki was arrested on several different occasions, but each time quickly released. Because of this repetition of arrest and quick release, poet-colleagues suspected that he was a Secret Police spy. However, this arrest pattern turned out to be a Secret Police tactic. Each further suspicion begat new suspicion among the haiku poets, so that the haiku groups lost some of their unity. These suspicions remained for some years after the war, but after Saitô’s death, and following a thorough review of the evidence, the Court in a 1983 ruling pronounced him innocent on all counts.

Figure 1: Additional Notes

1) Taisei Yokusankai (the “Imperial Rule Assistance Association,” or “Imperial Aid Association”) was created in 1940 by Japanese Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoye (1891-1945), who decided to end party politics in Japan. Under the Shintaisei Doctrine he moved to dissolve all the traditional parties. As a replacement there was the Taisei Yokusankai, a "right-socialist" entity or umbrella group. Its creation therefore was equivalent to making the Empire of Japan a single-party state. The President of Taisei Yokusankai was to be the Prime Minister, so at the time of the Conference, the President was Tôjo Hideki (1884-1948), then-Prime Minister of Taisei Yokusankai. This ‘entity’ also developed a public surveillance and monitoring system, known as Tonarigumi. (cf. Wikipedia: Taisei Yokusankai; in Japanese at: http://tinyurl.com/247zfs. Also see: Wikipedia: Tonarigumi; and in Japanese here: http://tinyurl.com/2qnttt.)